Review by Liza Lim

Forty people gathered expectantly in a quiet laneway tucked behind Melbourne’s vibrant Lygon Street. Like the stories of Polish writer Bruno Schulz in which reality hides extravagant strangeness, the door of a small terrace house opened into a ‘wunderkammer’, a veritable cabinet of curiosities in which each room contained twilight-zone performances of strange beauty, menacing wonder, as well as exquisite sensuality.

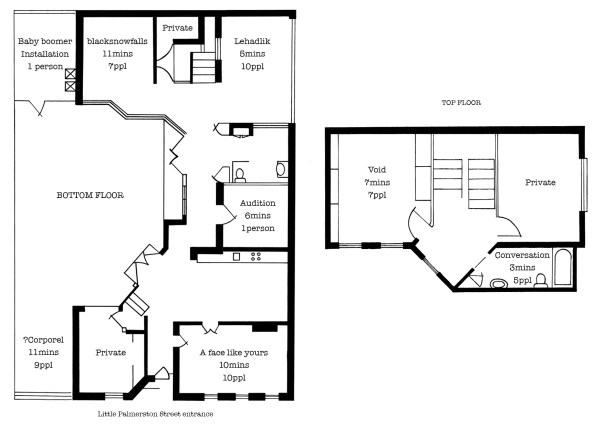

The event was DOMICILE, a programme of performances and installation pieces directed by Aviva Endean and staged with deft and imaginative flair in the house in which she grew up. The audience, provided with a plan of the house, wandered the rooms at will.

In the lounge room, a silent film, A face like yours (2015), made and performed by Aviva Endean and filmed by Christie Stott, flickered on the television. Earplugs provided allowed one to encounter a subtle internal world of sound as we mimicked the gestures and followed instructions on the screen to tap cheeks, hum, manipulate our lips etc. By way of contrast, in the back shed, one could interact more noisily with Dale Gorfinkel’s Baby Boomer (2015), a Heath Robinson-like contraption of foot pumps and balloons joined with plastic tubing to funnels, a battered tuba and a trombone, with garden irrigation switches allowing one to orchestrate changes to the wheezing combinations of sounds.

Out in the garage, Matthew Horsley could be found performing Vinko Globokar’s classic of body percussion ?Corporel (1984). On a loop during the 75 minutes of the event, this was a feat of concentration and commitment as he repeatedly slapped the different sounding surfaces of his bare chest, face and a satisfyingly resonant head. Another kind of skin percussion could be heard in the back bedroom inhabited by Matthias Schack-Arnott. In Wotjek Blecharz’s Blacksnowfalls (2014), hands and fingernails inscribe calligraphic movements onto a timpani giving rise to susurrations and sliding moans and creating a séance-like mood. A live video feed provided an additional level of visual detail, though for the audience of seven crammed into the room and sandwiched between a bed and mirrored wardrobe, proximity to the performer was intimacy enough.

Intimacy was the watchword for other works – two singers, Jenny Barnes and Niharika Senapati soaked in bubbles in the bathtub upstairs whilst exchanging enigmatic snatches of inhaled and exhaled sounds in Georges Aperghis’ Conversation (2004). In the next bedroom, a ‘grand amour’ was enacted in Endean’s Void (2015):

a pair of lovers approach in slow motion, the microphone held in the mouth of one (Aviva Endean) setting off feedback from the speaker held in the open mouth of the other (Alexander Gellman), reaching an inevitable denouement in a strangled kiss. Another ‘up-close’ experience could be had with Angelo Solari’s Audition (2014), staged as a one-on-one encounter with singer Carolyn Connor, with all the flavour of a Monty Pythonesque interview in a correctional facility. The queue was too long for me to get to it but my 13-year old son had a ball answering questions from the script and engaging in the staring contest. His verdict: ‘cool’.

Endean’s talents for creating an immersive atmosphere were perhaps most completely showcased in her composition Lehadlik (2015) in which the audience was invited to sit at a formally set dining table. The day’s coincidence with the start of Hanukkah provided an extra level of resonance to the work’s evocation of Jewish ritual: two lit candles were wired with sensors used to trigger recordings of incantations from the Torah, the sonic landscape enriched with Endean’s melismatic clarinet playing. The meditative ritual ended with a snuffing out of the candles through the bell of the instrument.

‘House events’ have long held an important place in experimental practice in music and performance, from concerts in Berlin apartments or New York loft-spaces to, more locally, the work of Aphids in domestic settings in the 90s and Chamber Made’s opera productions commissioned for people’s residences. The use of such spaces to shift the frame on audience interaction is a well played-out ploy, yet, DOMICILE refreshed this format through a finely tuned curatorial sensibility. The choice of repertoire, quality of performances, size and nature of the venue combined to create a very special evening that exuded hospitality and a sense of enchanted time. Adding to the sensory feast, there was even cake to share at the end. Cooked during the evening, it had suffused the house with a lemon-sweet tang that followed us out into the balmy Melbourne night.

Review by Liza Lim

DOMICILE

Fleur Ruben’s house in Carlton

Melbourne, 4, 5, 6 December 2015

Directed by Aviva Endean and presented as part of the New Music Network’s emerging artists program with support from Creative Victoria

Performers: Aviva Endean, Matthew Horsley, Carolyn Connors, Matthias Schack-Arnott, Alexander Gellmann, Jenny Barnes, Niharika Senapati

Set design, Romanie Harper

Technical design, James Paul

Artwork, Betty Musgrove