The first in a series of feature articles for Partial Durations.

By Matthew Lorenzon

This article began when a friend asked me “How much does it cost to commission a piece of music?” I felt that this might be a loaded question. I also felt that I could be trusted to give an impartial answer, being a musicologist and a music critic. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a clue. I usually come in at the end of the creative process, blissfully ignorant of how much time, sweat, and money has gone into it. So that I never again miss the opportunity to steer a budding patron of the arts towards a bevy of hungry musicians, I decided to ask around.

I quickly found that composers and ensembles were just as curious about commissioning as my friend. I also heard tales from frustrated patrons-to-be. To make this survey useful to as broad a segment of the community as possible, I interviewed a range of artists and donors. I began with student composer Peter Butterlake (name changed for anonymity), then interviewed one of Australia’s most commissioned composers, Gordon Kerry. I sought the advice of the emerging Syzygy Ensemble and the internationally-recognised percussion group Speak Percussion. I also spoke with composer and festival director David Chisholm about the role of festival in facilitating new work. Finally, I asked the philanthropists Tim and Lyn Edward about their experience with the commissioning process. I found all of the participants’ advice on commissioning so enlightening that I have included large swathes of the interviews below. Hopefully the text is navigable thanks to the extensive use of subheadings. Readers can also skip to the end of the article to find a handy list of commissioning “dos and don’ts” that didn’t fit in with the flow of the article.

Even though this article is framed as a prescriptive how-to guide to commissioning, I hope that it opens a discussion of the wide variety of experiences of private giving. If you feel that your experience is not represented here, please take to the comments.

What is a commission?

A commission is basically a request for a new piece of music. Every piece of music has to start someplace, and that place is not necessarily in the composer’s head. It may begin in a conversation between a composer and a performer. A work may even begin in a conversation between a private donor and an auspice organisation such as an orchestra, a festival, or a cultural fund. This piece may be delivered on paper, in a performance, as a recording, or any mix of the above.

In Australia, the commissioner is usually a public funding body, such as the cultural fund of a local council, or the Australia Council for the Arts. However, a growing number of private donors also directly contribute to Australia’s (and indeed their own) cultural life by commissioning new works.

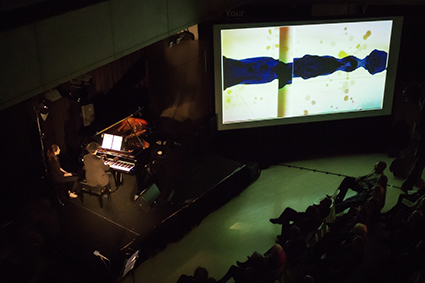

Tim and Lyn Edward have been commissioning new music since 2008. They commission the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s annual Snare Drum Award test piece. Recently, they also commissioned the percussion sextet with electronics Whorl Would Equal Reaches from James Rushford for Speak Percussion. They also have some more commissions in the pipeline. The Edwards see their contribution as “basically financial backing,” rather than artistic curation. They “pay the money to the company’s Administration and their Artistic team sources the composer.”

Not all commissions are so hands-off. Ughetti describes a range of criteria attached to commissions, from very specific commissions by institutions to open-ended commissions by individuals:

A commission could be anything from somebody coming in from the National Gallery of Victoria and saying “We’re doing an exhibition on postmodern European art and we need a composition that will go for this long, it will go after this speech by the minister for the arts [I would like to hear that speech], it has to be for mixed instruments and it has to be loud.” The other extreme would be an individual coming in and offering money for a new work without specifying anything.

Co-commissions

As well as institutions and individuals commissioning works, ensembles from around the world can also co-commission works together. To Kerry, this

mitigates the problem of pieces only being played once or twice and in a single location. People like Brett Dean, Liza Lim, Elena Kats-Chernin in particular have benefited from international co-commissions, which is great as the works are performed in Australia, Sweden, Germany, or the UK.

Syzygy Ensemble has also benefited from international co-commissions. Laila Engle describes a situation where

we played a work by an international composer and his publisher contacted us to say “I see that you played this piece. Would you like to get together with an English ensemble and commission a new piece?” The Brett Dean sextet that we are playing at the moment was co-commissioned by three high-profile groups: The Nash Ensemble in England, Eighth Blackbird and the Australia Ensemble. Splitting the cost and guaranteeing performances in multiple continents. That has really helped that piece come to life.

Festival commissions

Festivals not only auspice commissions, they can also commission new work themselves. The Bendigo International Festival of Exploratory Music (BIFEM) uses an innovative model of rolling over box-office takings from one year to commission works in the next. As Chisholm describes:

With the help of philanthropic organisations and government bodies, we are able to cover operation costs. Box office sales then roll over to commission new works for the next year. We can’t use Australian money to commission non-Australian composers, but we can use box office takings to do that. There are about five or six new works in the festival, which is absolutely fabulous.

Sharing the risk around

Though the donor expects no monetary return from their gift, donors and performers sometimes exercise risk-management when commissioning new music. In his 2004 Peggy Glanville-Hicks address “Why Bother?”, Julian Burnside remarks that a commission is unlikely to be a completely satisfactory experience for the commissioner if they never hear it. His suggestion that groups of donors commission new works together is not only a pragmatic way in which someone of almost any financial means can contribute to new work, it is a pragmatic way of guarding against a disappointing commission. Engle has noted the move away from single-patron commissions to commissions from multiple donors:

Applying for private funds can be a bit like applying for grants. People don’t want to give you 100% of anything. They don’t want to take all the risk. There is a big push in Australia to couple public funding with private sector funding, which helps share the risk around.

Crowd-funding is an extreme version of distributing risk. Both Syzygy Ensemble and Speak Percussion just completed crowd-funding drives with Creative Partnerships Australia. Creative Partnerships Australia matched private towards these campaigns dollar-for-dollar. The Australian Flute Festival successfully crowd-funded a commission by Paul Dean as a test piece for a competition, the competition’s entry fees effectively paying for the work. The Bang on a Can People’s Commissioning Fund is an ongoing platform for small-scale donations towards new work. While crowd-funding harnesses the significant—but further distributed—resources of a musician’s networks, its principles are the same as other forms of private fundraising: donations result from fostering relationships. Repeated crowd-funding drives without giving back to one’s donors through a performance of new work will result in donor-fatigue.

Managing relationships: The commissioner, the composer, and the performer

The principal risk involved in a commission is that it is not performed. A commission is therefore ideally a triangular relationship between the donor(s), the composer(s), and the performer(s). Artistic directors of ensembles, festivals and agencies are helpful in facilitating these relationships. The Edwards state that they are “more likely to commission through an organisation because we don’t feel we have the expertise to go directly to a composer.” As the artistic director of Speak Percussion, Ughetti is something of a match-maker. All of the private money that Speak has received has gone straight through the ensemble to composers:

It’s hard, it’s not a nice thing to do, to ask people for money. It’s way harder when you have to ask for money for yourself. If you ask on behalf of somebody else, a young composer for instance, if you say “you will support a great talent and in years to come you will be responsible for making an Australian cultural asset,” then that is a much more comfortable situation. I think that to date, all of our private donations have gone straight in and out to composers. It has never remained in the ensemble.

Musica Viva is instrumental in auspicing commissions for some of Australia’s most established composers. Even when commissioning work through Musica Viva, the commissioner may be a long-term friend of the composer. Kerry explains that

when Carl Vine took over as director of Musica Viva he instituted the “featured composer” program. That meant that each season would feature 4–5 works by a composer. Each season became a little retrospective of a composer. Some of the commissions I have received through Musica Viva, including through the Featured Composer program, were more specific than others. It’s not like in the visual arts where the commissioner says: I don’t like that, can you put more pink in it.” Fortunately that doesn’t happen. I did, though, receive a commission from a friend in Sydney who inherited some money and her partner was turning 60. She commissioned a string quartet work through Musica Viva and under the circumstances it was appropriate that the piece be celebratory.

BIFEM’s private commissions have been the result of several years of building trust between the audience and the festival. Chisholm stresses the importance of the artistic vision of the festival, ensemble, or project in fostering private support.

This year we’ve been able to commission two overseas artists as well as locals. There is a couple, regular folks from Essendon West, who are regular patrons of the festival. They came to us not knowing how to commission a work. I showed them the Australia Council guidelines and previous commissions within the festival so they had a sense of scale around the process. But it’s really about these people coming to the festival and deciding that it is something they want to do. It’s a hard thing to go and ask people for. All fundraising is about relationships and they all take time. One of the great failures of some arts organisations is that they appoint a development manager thinking that somehow their Teledex is going to bring them relationships. They may have the contacts, but it’s all about what it is that you’re doing that makes them want to invest in you.

Commission a piece, get a tax deduction

One of the benefits of commissioning a work through an auspice organisation such as certain orchestras, ensembles, festivals and cultural funds is that one receives a tax deduction. The Edwards explained that tax deductions are less of an issue now that Tim is retired, but that while he was working “the deduction was definitely a factor.” Chisholm explains:

Make sure you can commission through an organisation or auspice organisation that has tax deductible recipient status and charity tax concessions. It’s possible that you maximise your tax benefits that way. For $2,500 out of your pocket, you can get a $5,000 work. You would have to pay that tax anyway, here’s a way of controlling where it goes.

Whether you commission a work directly from a composer or through an organisation can depend on how much control the donor wants over the commission. As Ughetti describes the situation:

If someone donates to an individual they will not receive a tax deduction. If they donate to an organisation, they receive a tax deduction but they cannot tell the organisation how to spend the money. That would no longer be a gift, they would be buying something. There are some individuals who know who they want to commission and why. It could be a family member or someone who has seen the artist grow up for years, it could be an artist that they love. But that artist might not be a good fit with an organisation. The organisation and the individual would definitely have an understanding, they have a duty to respect each others’ wishes, but the patron does not have ownership over the work and cannot tell the organisation how to spend their money. Often both the organisation and the donor have similar values. It only becomes an issue when there are conflicting wishes.

If you arrive at an understanding at the very beginning, if you say “there is this fantastic composer, we want to commission them, would you be able to give us some money?” If we then volunteer to pass all of that money on, they get the tax deduction and we get the commission that we would have had to fundraise for elsewhere.

It all starts with a relationship

Even when a commission is made through an auspice organisation, a personal connection is central to the project. Tim and Lyn Edward state that they are inspired to commission works because of their love for percussion and also

to encourage developing performers, see new works added to the repertoire and support individuals and organisations we have come to know.

The Edwards frame the origins of their commissions in terms of personal relationships:

Rob Cossom, the initiator of the Snare Drum Award, put out a call for someone to fund the commissioning of an annual test piece, saying it would add prestige to the event (we now believe it was also necessary for the award to continue) and we decided to take it up.

We met Eugene through John Arcaro and greatly admire him and the work Speak Percussion do. When we expressed interest in contributing, Eugene suggested we do so with a new commission.

Fostering direct relationships with commissioners is as important for established composers as it is for emerging composers. Kerry spoke about the interpersonal origins of some of his most recent commissions:

If the commissioner knows the composer and likes his or her work, then that is usually why that composer gets chosen. In 2012 when I was touring with various groups, when the String Quintet was being played, I would stand up and make this speech about how philanthropy was a wonderful thing and if people wanted to throw money at me I’d be standing by the bar at interval. In Queensland someone came up to me and said “Yes, tell me more,” because she and her husband have a weekender in the Sunshine Coast hinterland and she said it’s just full of birdsong and they’d like to celebrate that. So I got her to buy a Zoom and she went out and recorded an hour or two of birdsong, which I listened to and played around with on Audacity and found a whole lot of hidden musical moments and turned that into a piece. That was a fairly clear brief and a very nice one.

Relationships between composers and performers also need to be carefully managed and are an often-neglected part of the commissioning process. Several interviewees commented on how composers and performers form communities of stylistically-aligned individuals. These relationships develop gradually over time. In Ughetti’s case, it took years before Ughetti and the composer Robin Fox were able to decide how they wanted to work together.

Most composers and performers are looking for like-minded individuals. A particular group with a particular aesthetic will attract a particular kind of composer. There will be composers who think “well, this group will never perform my music because I just don’t fit into their style.” So, a lot of it is about following an artist and through following them you inevitably meet them or start an email dialogue with them and through that you either form a friendship or you form a relationship that has some element of trust and respect. Out of that can come the will to work together. Robin Fox and I have collaborated once, but it took us five years to figure out how we wanted to work together and I’ve been an admirer of him for ten to fifteen years and he’s known about my work too, so there was mutual respect there, but we didn’t know how or when we wanted to work together. In some instances, depending on the context of the project, some funding might become available and then you look at how best to spend it.

Show me the money

So perhaps you have a composer or auspice organisation in mind. How much does it cost to commission a work? The Australia Council for the Arts publishes their own composition fees, “which probably haven’t kept up with CPI,” according to Kerry. The rates can be found online here. The Australia Council calculates the cost of a commission according to the number of independent voices in the piece and its duration in minutes. The table below shows some actual examples of commissions that the interviewees were aware of. I have calculated the Australia Council’s rates for the same works myself in the right-hand column. As you can see from even this limited data, the Australia Council rate tends to sit at the lower end of what established composers tend to be paid. Senior or mega-famous composers tend to attract much more funding, though still an order of magnitude less than their colleagues in the visual arts.

| Career stage |

Independent parts |

Duration |

Time Spent Composing (full time) |

Commission received |

Australia Council rate* |

| Emerging composer |

Solo guitar |

15 minutes |

Two months |

500 |

6,795 |

| Various composers |

Solo percussion |

8 minutes |

|

1,000 |

3,624 |

| Emerging composer |

percussion sextet and electronics |

30 minutes |

|

5,000 |

15,420 |

| Established composer |

Solo percussion |

10 minutes |

|

2,000–8,000 |

4,530 |

| Established composer |

Solo performer (long-form dramatic work) |

60 minutes |

One year |

28,000–30,000 |

27,180 |

| Established composer |

Orchestra and chorus (long-form dramatic work) |

90 minutes |

18 months |

35,000–40,000 |

58,050 |

| Senior composer |

Twelve

percussionists |

10 minutes |

Several months |

20,000 |

5,840 |

| Very, very famous composer |

Percussion quartet |

12–16 minutes |

|

60,000 |

6,168 |

Table: Details of some commissions discussed during research for this article. *Not necessarily received. This column is for comparison.

Early careers and murky economics

Money may not change hands at all if the commissioner is an ensemble or a performer. Engle describes the complex transactions of intangible assets and “reciprocal resources” that can take place when Syzygy Ensemble commissions a work:

In the end it’s all about reciprocal resources and relationships. When you want to commission someone, it is normally someone you know, who you have a deep respect for, whose work you admire. Usually this feeling is reciprocated and both parties gain from the experience without any monetary exchange necessarily taking place.

When Syzygy started, we had a launch party and a lot of composers who knew about the group and who were interested in performing new music approached us. You do get a lot of people just sending you scores. We have worked with composers where we have applied for funding and when it hasn’t arisen they have composed it for free. In return, we played on her album for free, so it was an in-kind exchange.

Kerry remembers his early compositional career as “a mixture of luck and making your own opportunities”:

For a young composer, as I was then, it was a matter of knocking on doors a bit and saying “listen to my choral music.” I had also written on spec for Elision and the “New Audience” concerts—or as we called them the “No Audience” concerts—at Melbourne University. A group of composers who were students at the time, including Liza Lim and myself, began writing for Elision. They built up their repertoire and we built up great skills. It meant that I had a body of contemporary mixed ensemble pieces. Then ideally, one starts attracting the attention of mainstream groups and funding bodies. I started getting commissions for groups like the Australia Ensemble. That broadened the field for me a bit. Also, I had written some works for the Philharmonia Choir, which included works for choir and orchestra, which attracted the notice of ABC Concerts, which in those days managed the state orchestras.

When they are paid, emerging composers enjoy a somewhat higher proportion of in-kind to monetary support as part of their commissions. Butterlake’s first commission came out of the pocket of a friend, a young guitarist. Though the pay was small, both parties benefited from the commission. In Butterlake’s words, commissioning a new work “is as much a milestone for a young performer as it is for a young composer. They want to build repertoire, they want to be the first person to play something.”

Early-career composers may also receive commissions as a result of competitions and calls for scores, both of which begin as unpaid opportunities. Engle explains:

No money changes hands in a call for scores. Those opportunities are usually directed towards developing artists who need time with musicians to ask questions and then, once they’ve proved themselves, that’s a good time to commission someone. These are also in-kind transactions. It may cost $150 per person per call to rehearse a piece. That’s $600 for one rehearsal of a quartet. We did workshops at Melbourne University a few years ago and they just give us a lump sum to play six or seven new works. We say “we will spend one rehearsal preparing all of this,” then we do the workshop with a conductor so that we can get through everything quickly. We then look for funding afterwards to present that work, because the presentation and recording of a work is valuable to the composer. That is something that they would spend their money on, if they had it and it was a transactional relationship. That would be an important part of their portfolio.

We did a workshop at the Kingston Arts Centre where we put out a call for scores. It was open to anybody. We had a guy in his eighties who had never had anything performed professionally, but he had been writing for his church group for many years. We had a teacher from Sale, Gippsland, who wanted further development. We had university students. We workshopped all of those pieces over a series of weekends and then we chose outstanding entrants and programmed them in a performance.

While recognising the important educational role of early-career unpaid performance opportunities, Butterlake understands that there is

a big leap of faith involved in submitting to a Call For Scores or a competition. The Soundstream Collective’s recent competition received 27 or 28 entries, six of which were performed. Three composers from this group were then offered commissions of $5000, $3000, and $1500 for new works.

There is definitely an imbalance of unpaid opportunities. But they are the standard steps that composers go through: AYO, TSO, MSO, Ensemble Offspring and SoundStream. There are really established opportunities in Australia. You do those, then you go overseas and take up similar opportunities over there: Bang on a Can, Royaumont. They are all unpaid opportunities as well. Maybe at the end of that you will have generated enough interest in your work to actually get paid.

Despite competitions and calls for scores being primarily educational opportunities, it is interesting to note that Engle and Butterlake both discuss them in terms of managing risk. Engle talks about composers proving their worth and Butterlake sees competitions as primarily about raising the composer’s profile. It is of course ludicrous to think that the quality of a composer’s work is going to shoot from worthless to payable after a couple of these opportunities, which sometimes amount to a play-through and a pat on the back. There is thus considerable value in commissioning early-career composers through ensembles who have close links to rising generations of composers.

Established careers and murky economics

Even well-established composers and performers often subsidise their own work. Engle recalls asking

a prominent performer about how they go about commissioning works and she said “It matters how much I want it. If I really, really want it and I can’t fund a particular artistic relationship with someone, then I just pay for it myself.” […] There isn’t enough recognition of how much artists subsidise their own work.

Just as a more established composer attracts a higher fee, so too does social distance increase the funds needed to secure a commission. Engle explains:

As soon as you approach someone with a higher profile or who is more distant from yourself, more resources need to be involved. You might need a funding partner on board to manage that three-way relationship between the expectations of the person commissioning the work, the expectations of the composer, and the performer.

Ughetti outlines a similar dynamic, stressing the importance senior composers place on the performance outcomes of their work.

Every conversation is different. Every conversation brings into account all of the previous relationships that you might have had with that person: your awareness of their work, what is motivating you to commission them in the first place, what’s motivating them to work with you, and then an idea that everyone will be excited about. Sometimes just the notion of a new work is enough to get people excited, but better-known composers will often be attracted to a strategically-sound project that is already coupled with an outcome. When approaching high-profile, international composers, right from the beginning I am talking about recordings, performances and tours before we’ve even thought about what the work may be. For young composers, the idea of being paid to write a piece is already great for their career, so the nature of the conversation changes dramatically.

As a senior Australian composer, Kerry also advises having a “sliding scale” depending on who is funding a work:

When dealing with philanthropic people one does need to be prepared to have a sliding scale, on the principle that it’s better to write a piece than not write a piece. Obviously if a particularly munificent patron comes along one takes what is offered, and the fees offered in, say, the UK, are generally considerably higher than here. When dealing with people who haven’t commissioned a work before—especially if they’re not especially wealthy—one tries to come up with something affordable for them that still makes it worth one’s time to write the piece. (Even corporate sponsors have been known to baulk: One colleague produced an orchestral work a while back, which would have taken up to six months to write, and the orchestra’s AA had to bite the tongue when, handing over the giant novelty cheque, the sponsor said “that seems like a lot for a piece of music.”) So in some cases one has to gently explain that writing music is labour-intensive, and there is a lot of time spent doing things that might not look like work but which prepare the way, and that one would never calculate an hourly rate for composition as it would drive one to suicide. Or law school.

Kerry’s private commissions have largely appeared later in his career. This reflects the changing face of Australian philanthropy. The ABC used to play a much greater role in supporting Australia’s major orchestras, including commissioning new works that would then receive two or more performances by different orchestras. As Kerry sees it:

Now, with every orchestra independently managed, there is not as much incentive to commission new work as there was back in the ABC days, when a new work would receive several performances and several broadcasts in a year. But there are some new initiatives from the orchestras for young composers: MSO has teamed up with the Cybec Foundation, for instance. There are those opportunities that weren’t there before.

In Australia, private commissions may occur much later in a composer’s career. He sees this as partly owing to the fact that,

though the orchestras and major organisations are largely publicly funded, they have to trade into surplus, they have to behave like businesses. They tend to be little inclined to spend money on commissions or at least have to rely on philanthropy.

Though there are still many, if not more opportunities to be commissioned, Kerry feels that there are less opportunities to hear repeat performances of works that are important parts of our cultural heritage.

We all face the problem of the lack of programming and of performance opportunities for Australian composers. There is a lot of orchestral music by my colleagues that I’d like to hear more of. It is great that groups like Plexus and Syzygy are commissioning new work. But there is a lot of stuff that we should hear for the benefit of our own cultural understanding that is no longer performed. There are parts of numerous works by Australians that are no less palatable than something by a nineteenth-century composer, so why not program them? There is the problem of audiences wanting familiar names on their programs. The Australian Chamber Orchestra put some obscure eighteenth-century composer on a program several years ago and everyone thought it must be a new music composer. They had to say “it’s okay, it’s full of tunes.”

Who pays for performances?

Despite the importance of performance to the overall success of a commission, performance costs are rarely included in the commissioning fee. Ughetti details the financial pressures of presenting new work:

An important element of a commission is that it has to be learnt and presented. The learning and presenting can often be much more expensive than the writing of it. In Speak’s case, if we commission a trio, it might take three weeks or three months for the composer to write. It could even take a year, but generally between three weeks and three months. We might then have two weeks of solid rehearsals for three players, that’s six weeks of rehearsal to be paid for. There might be a publicity campaign, a venue and a lighting designer that cost thousands more dollars. That’s a really important part of the mix and often composers are more interested in the fact that their work will be presented than receiving a strong fee.

Performance costs are almost never factored into commission costs. Some commissions don’t have a deadline. It’s pretty hard to publicise and plan a performance of a work before you’ve even written it. It might be much longer, or technically difficult, or not suited to the venue. Or, as happens with many pieces, they are delivered late. Sometimes after the deadline of the performance. Depending on the project, presentation costs might be bundled into the whole conversation, into the whole budget.

Think big

The composer David Chisholm avoids the problem of who will play his music by focusing on long-form works over which he has control of the outcomes. It is also easier to secure funding for one large work than it is many smaller ones.

I made a very clear-minded decision many years ago to focus on long-form works. I felt that there was a better chance of securing funding if I was ambitious and there were outcomes assured for the work. I also decided that I didn’t want to fill my catalogue with ten or twelve-minute works. I came to composition late. I studied early but spent a long time at dance parties instead of composing. When I hit 29 and wanted to get serious about my practice, I realised that the best way to get attention and make leaps and bounds was to produce long forms. I feel more comfortable composing like that as well.

Long-form work means that I can self-produce and set up the creative partnerships myself. It seems more sensible to create a work that people will come to and remember than a ten minute work that they might not. Theatre and dance practitioners produce long-form work without even blinking an eye. My big compositional heroes were Wagner and Messiaen and the works of theirs that I was most impressed by were the really big ones. I have always locked composing into presentation. I was speaking to a donor who said that half the works he had commissioned had not been performed. I think that says a lot about his commitment to nurturing the arts, but it is also an indictment on the arts sector for not finding ways to link their work to outcomes.

It is almost a waste to give people small amounts of money. Why commission small works when it’s never going to have an outcome? It is going to take the sector a while to adjust to the thinking that they can ask for a lot of money rather than a little amount.

Dos and don’ts

If you have made it this far, you would be aware of the most important “do” in commissioning new work: Ensure a performance outcome. For a composer, this might mean taking control of the performance of your works (in Chisholm’s case) or liaising closely with ensembles to ensure that somebody has agreed to perform your work. Several more important messages came through in the interviews. Seeing as they did not fit neatly into the above text, I have provided them here as series of pithy “dos” and “don’ts.”

1. Do: Consider commissioning a longer work

Kerry: There is a preponderance of 10–12 minute pieces, going back to the 1970s. If I’m commissioned to write a 10–12 minute piece, I write a 10–12 minute piece, because if I turn around and say “sorry, it’s half an hour long,” then it’s too hard to programme. On the other hand, I saw a blog somewhere that said “Gordon Kerry can only write 10-12 minute pieces.” But that’s not true! Some of my pieces are 20, 90 minutes long. You do have to sell tickets but audiences today are much more open to new music than they were 30 years ago. There has been a stylistic rapprochement with the audience.

2. Do: Be cautious around universities

Some university composition departments facilitate significant commissioning prizes for young composers. These include the Dorian Le Galliene composition award and the Albert H. Maggs. In these cases, substantial funds have been provided to the University for valuable, ongoing commissions programs. Universities have, however, been known to struggle to accommodate smaller donations for individual commissions. For one-off commissions, consider getting in touch with one of the major orchestras or ensembles that work regularly with young composers, including Speak Percussion (Melbourne), Ensemble Offspring (Sydney), Syzygy Ensemble (Melbourne), Decibel Ensemble (Perth), or Kupka’s Piano (Brisbane).

3. Don’t: Be too prescriptive when commissioning work.

Chisholm: It is important that your commission does not predicate style or content too strictly. You are not just investing in the work, but in the individual. Ensure that the relationship you develop with your commissioners is one where you have artistic freedom. Nothing wrong with writing jingles, but that’s a direct transaction and commissioning is not a direct transaction. It is buying an artist’s time to pursue their practice within certain constraints. Of course I will write chamber music for someone with a special interest in chamber music, but I will decide the content of that chamber music.

4. Don’t: Composers, don’t cold-contact an ensemble with a piece. Do get to know them.

Ughetti: Composers cold-email ensembles, though often it is in the form of a media kit. “Would you consider performing this piece?” I’ve had composers I don’t even know say “I’d like to write you a piece, I’m ready to go.” It is very rare that anything comes of these approaches. It would be like going on a date with someone who just emailed you. It’s lovely, but you might want to know who they are first.

5. Do: Keep your commissioner happy.

Kerry: If someone wants to commission a piece they are doing so out of a feeling of good will towards the composer/art form/performer, and if that is successful they may want to do it again. […] On occasion, writing a slightly longer piece than the commissioner can afford can be a nice gesture of good will back, as can personalising the work in some way.

6. Don’t: Chase other people’s commissioners.

Chisholm: Composers sometimes identify a donor of mine and go chasing them. That’s really tacky. Have a bit of solidarity and respect for the fact that these relationships aren’t necessarily transferrable. It’s advisable to cultivate your own relationships.

7. Do: Make sure philanthropic bodies support something central to your project.

Chisholm: Certainly philanthropic organisations really need to know that what they’re doing is playing a vital role, even if they are partnering with government agencies they need to know that they’re going to pay for a very important aspect of the project.

7. Finally, Do: Commission new music, for your own sake as much as anyone else’s

The Edwards give the following words of advice:

Go with your heart and your soul. Choose instrumentation and genre you are passionate about (within budget constraints of course) and, unless you are dealing directly with the composer, feel you can trust the organisation you are dealing with to administer it but to keep you in the loop.

Ughetti notes the considerable benefits of supporting new music to one’s personal culture, as well as the wider community’s.

We’re such a wealthy country and we’re so materialistic and ambitious, which in its best form is a good thing, but our cultural and spiritual dimensions have suffered from this. With this money, our lives could be so much richer and more beautiful than they currently are. Our standard of living would drop a little. We might have one less TV or not quite the latest Lexus, but the vibrancy and depth of our culture would be greater. People work so hard they don’t have time to engage with arts and culture. People need to have an awareness of their own culture, of their physical culture, of music, art, fashion, and design.

Though the benefits for composers, performers, and donors are great, commissioning new music is a strategic minefield. Fortunately there are programs (and now a Programme*) that aim to make this process easier. Whether you donate through Musica Viva, directly to a composer, or throw a few dollars into a crowd-funding campaign, it will probably be because you know the artists or are a fan of their work. To quote Engle, developing these relationships is “one of the most important extra-musical skills” of a contemporary musician. Above all else, make sure that this great new music is shared and heard.

[* I began this article well before Senator George Brandis announced his National Programme for Excellence in the Arts, a programme that is funded directly at the cost of Australia’s independent, peer-reviewed arts funding organisation the Australia Council for the Arts. This article is by no means an endorsement of the continued division and erosion of public funding for the arts. July’s feature article for Partial Durations will look more closely at Brandis’ changes, which put small-medium music organisations—within which almost the entirety of contemporary art music is created—at risk.]

![TURBULENCE [5]_Page_1](https://partialdurations.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/turbulence-5_page_1.jpg?w=604)

![TURBULENCE [5]_Page_2](https://partialdurations.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/turbulence-5_page_2.jpg?w=604)

![TURBULENCE [5]_Page_3](https://partialdurations.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/turbulence-5_page_3.jpg?w=604)

![TURBULENCE [5]_Page_4](https://partialdurations.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/turbulence-5_page_4.jpg?w=604)

![TURBULENCE [5]_Page_5](https://partialdurations.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/turbulence-5_page_5.jpg?w=604)

![TURBULENCE [5]_Page_6](https://partialdurations.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/turbulence-5_page_6.jpg?w=604)

![TURBULENCE [5]_Page_7](https://partialdurations.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/turbulence-5_page_7.jpg?w=604)